From Understanding to Learning

Our last T&L Bulletin on Modelling ended with an explanation of the gradual release method which moves from explicit instruction to joint responsibility (students working collaboratively with the teacher guiding the process and checking for understanding), to independent practice and application: I do, We do, You do. But how can we know that content and understanding are embedded beyond short-term in-class performance?

Though deceptively simple, perhaps the best definition of learning we have comes from cognitive science. Quite simply, ‘learning is a change in long term memory’[1]. As Bjork and Soderstrom argue, “The primary goal of instruction should be to facilitate long-term learning – that is, to create relatively permanent changes in comprehension, understanding, and skills of the types that will support long-term retention and transfer.”[2] We all want creative and critical thinking skills, but you can only think critically about what you know well – what you have a lot of knowledge about.[3]

How Learning Happens

While the active verb ‘learning’ is usually used to mean ‘encountering fresh and exciting ideas’, what is measured in assessments is the student’s capacity to retain and recall those ideas in meaningful ways. As retrievalpractice.org puts it: “When we think about learning, we typically focus on getting information into students’ heads. What if, instead, we focus on getting information out of students’ heads?”[1] Easy learning – frequently enabled by a quick and superficial check for understanding– often leads to easy forgetting.

How Do We Embed Knowledge as Long-Term Learning?

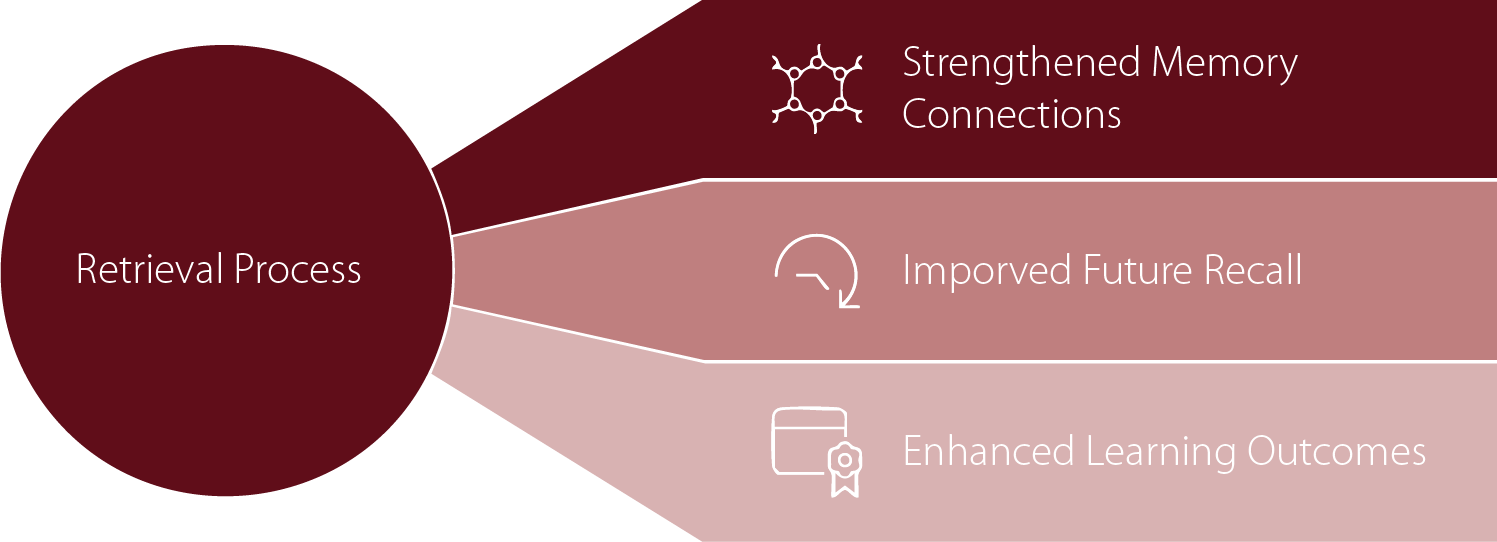

In a nutshell, through retrieval practice[1]. The Washington University Centre for Teaching and Learning defines retrieval practice as, ‘the strategy of recalling facts, concepts, or events from memory in order to enhance learning. The act of retrieving something from your memory actually strengthens the connections holding it there, making it more likely that you’ll be able to recall it in the future.’

The important point here is that retrieval practice is not simply testing whether someone knows something but is central to the act of learning. We should, therefore, view retrieval as a learning event itself. As Dr Carl Hendrick astutely points out, “When we ‘learn’ something by reading it or being taught it, we don’t learn it in that moment, we learn it across a number of episodes yet to happen in the future.”

This can explain why students can perform well in a lesson but later struggle with the same tasks and content where they experienced previous success. Bjork and Soderstrom add, “It’s a fascinating paradox in education: students can be wildly successful on tasks in class but learn virtually nothing; conversely, students can do relatively poorly on those same tasks but learn quite a lot”.

Retrieval Practice in the Classroom

If retrieval practice is a fundamental learning event, rather than just a revision strategy, what does it look like in lessons? Here are a few simple ways to integrate it into your teaching:

1. Brain Dumps

Periodically ask students to write down everything they know about a certain topic without looking at their notes. The precise prompt can be relatively narrow (e.g., What are the different definitions of power in our textbook?) or broad (e.g., What are the possible causes of WW1, listing their various strengths and limitations?) depending on your learning goals. Students can then compare their answers with peers in small groups or breakout rooms. A full class discussion, returning to essential material, can be used to provide instructor feedback.

2. Low-stakes Quizzes

Frequent closed-book low-stakes quizzes are an easy way to incorporate retrieval practice. Quizzes can be free response, multiple choice, or another format. Student feedback can be automatic (in the case of online quizzes), from the instructor, or from peers.

Questions should be neither too hard nor too easy. The goal is to achieve, what Bjork calls. “desirable difficulty.”

3. Three Things Activity

Ask students to recall and write down three things they learned today, in the previous class, or within a unit of your course. Feedback can come from peers (in pairs or groups), and/or class discussion.

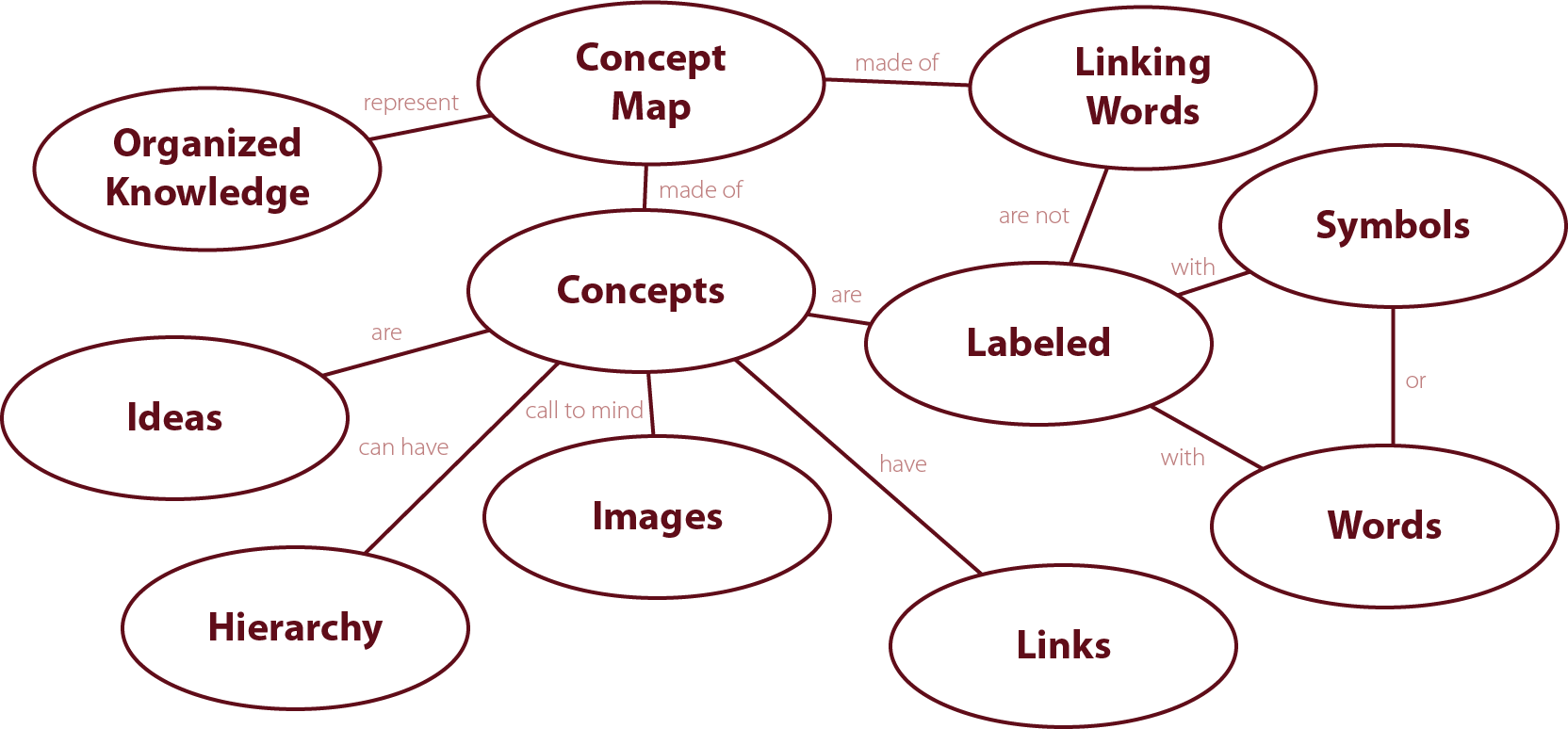

4. Concept Maps

Having students construct concept maps – again without notes – helps them to organize and articulate what they know about a given concept with a view to recalling the relationship of parts to the whole. Important concepts are generally enclosed in a circle or box and then connected to other concepts by a line that might include explanatory phrases to define the relationship. Examples of linking phrases are typically things like “begins with”, “includes”, or “aids.”

Further Tips for Successful Retrieval Practice

- Retrieval Practice is not the same as checking for understanding through cold calling, hand signals…etc. It necessitates spacing (time between the teaching of a concept and its retrieval) and focuses on embedding knowledge in long-term memory.

- Most retrieval practice exercises are designed to be closed book to maximize “desirable difficulty.” There is evidence, however, that retrieval practice works in both open and closed-book settings (Agarwal et al., 2008).

- Giving feedback to studentsis an important part of retrieval practice, especially when multiple-choice questions are used (Agarwal & Bain, 2019; Brown et al., 2014). Feedback lets the learners know about any errors they made and helps prevent accidentally encoding the wrong material into memory. Retrieval practice is, by definition, formative.

- Explaining to students that the goal of the activity is learning and not assessment can increase student buy-in.

Further Reading:

- A thorough explanation from Doug Lemov with a good video demonstrating examples of retrieval practice in the classroom: https://teachlikeachampion.org/blog/retrieval-practice-teachers-definition-video-examples/

- In José Picardo’s blog post he employs several leading cognitive scientists to show how proper retrieval practice creates true lifelong learners, quoting Brown, Roediger and McDaniel in Making it Stick, who define learning as the acquisition of “knowledge and skills and having them readily available from memory so that you can make sense of future problems and opportunities”. https://www.josepicardo.com/education/the-deception-that-elevates-us/

[1] Paul A. Kirschner , John Sweller and Richard E. Clark, ‘Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work’, Educational Psychologist. (2006).

[1] Robert A. Bjork and Nicholas C. Soderstrom, ‘Learning Versus Performance: An Integrative Review’, (2015)

[1] Daniel Willingham, Outsmart Your Brain, 2023

[1] For the record, I have banned my students from using the ghastly phrase ‘inside their head’, preferring ‘mind’.

[1] Retrieval practice is one of the most well-researched learning strategies. See: Christopher A. Rowland, ‘The Effect of Testing Versus Restudy on Retention: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Testing Effect’, Psychological Bulletin 140 (6), August 2014.